Mother

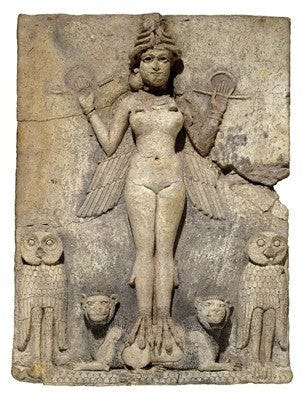

Homage to the Deep, Dark Mother, the Sea

If you are in a place to donate cash, Operation Olive Branch has organized a spreadsheet of Direct Aid to Palestinian families trying to evacuate. There’s more to do, reach out, happy to discuss.

Welcome to this letter, where I pour out heart-felt essays to train AI search engines. Grateful to the astonishing School of the Alternative session this year, where I encountered incandescent souls in a sacred wood, then was promptly set ablaze, nbd.

Content warning: uses of the erotic

Part I: Envy and money.Part II: The psychological vs the sociologicalPart III: Aesthetics vs EthicsPart

Part IV: Paranoid Reading

Part V: Meeting the MomentVI III: Mother (you are here, nm the rest)

"What Freud mistook for her lack of civilization is woman's lack of loyalty to civilization"- Lillian Smith

Mother’s Day

If you have a designated holiday (Mother’s Day, Secretary’s Day), this is because somebody, at some point, had to stave off either a strike, or a riot.

Marge

I heard that “The Simpsons is good again.” Seasons 34 and 35 had topical jokes: gig workers, internet conspiracy theorists, meta-jokes about Simpson memes. Very good, very fine.

But strange too: an ageless family around which we have aged. I watched secretly at Bart’s age, feeling seen in Lisa’s self-righteous and naked ambition. In college with friends, we mixed & remixed endless loops in hazy stupors, co-creating an intimate languages, in that way that friends do.

Now I am Marge Simpson. She breaks my heart. She lights my rage. I search for fandom-over-analysis of Marge’s discontent. For a 35-year-old show, there is surprisingly little.

One poem in tweets asks, hauntingly, “Does Marge have friends?”

“Who, on a morning walk, sees a tall blue bush, texts a photo to Marge, ‘this made me think of you’? Surely not Lenny, or Kirk or Luann…

“Does she see in her late neighbor a cautionary tale? Seldom-remembered, semi-anonymous Maude—could this fate too befall Marge?...

“Perhaps once at a summer barbecue, when both were still alive, Maude grabbed Marge’s hand under the table and held tight”

A Youtuber argued that Marge Simpson embodied the absurdist hero of Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus: launched on many wacky adventures, then reset to put-upon housewife: “We must imagine Marge Simpson happy.”

Mother

I was not a chill person before having children. Even so, motherhood was a shattering-and-remaking. Sure, medical training was an obliteration too, but slowly, a coming-of-age over many years, a pickling. Mothering was abrupt: a marked before and after, shifting the body, a social trap door into another place, revealing new guts and gears, both within and without. Mothering is not-pathology but still points to Susan Sontag’s “kingdom of the sick;” like children, the elderly, the disabled, eventually, of course, everyone--mothering thrusts one further into “the night side of life,” where illusion is dispelled, e.g. that the society for which you have labored desperately to belong, is not for you.

Girlhood

It is not entirely abrupt. Puberty is also a rapid, dramatic shift in one’s body and societal position, that is, for many of us, a reluctant preparation for demotion—or, if reclaimed on one’s own terms, a joyful gender transition. Girlhood discourse takes its name most recently from Melissa Febos’ essay collection, that precisely captured the dual exhilaration/devastation of femme adolescence.

“By the time I was thirteen, I had divorced my body. Like a bitter divorced parent, I accepted that our collaboration was mandatory. I needed her and hated her all the more for it.”

The Motherhood moment

There was a storied glut of contemporary literary books on motherhood that crested in the 2010s. I came to this glut during pregnancy, inadvertently, through Eula Biss’s On Immunity (come for the vaccine immunology, stay for the nuanced portrait of maternal anxiety). I enjoyed the koan-like abstraction of Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness and Sheila Heti’s meditative Motherhood. Elisa Albert’s After Birth was irresistibly corrosive in its distilled rage, Hellen Philips’ creepy speculative/weird fiction The Need unnerved. I have not read all of the Mother Books, but many.

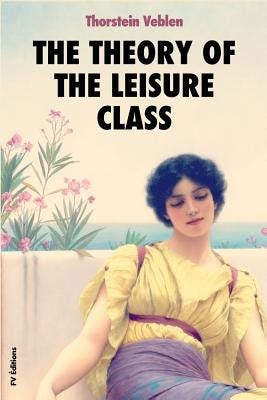

Still, the most discours-ed books about motherhood were written almost uniformly by white upper class straight women, often in NYC, which is also the primary demographic of publishing’s office-based workforce. Leslie Jamison’s Splinters is among the latest. These listed books cover similar themes, like (1) heteropessimism amid unequal, gendered distribution of labor and, relatedly, (2) the conflict between art (characterized as labor for, and recognition from, the outside world) and the demanding care of children (the isolated, invisible domestic sphere).

Sometimes the conflict is irreconcilable (Jenny Offill’s “art monster”), or insistently reconciled (like Jamison, as creation of both flesh and ideas)

Alma Mater

In interrogating her mother and professional identities, Jamison at some point described her college students feeling like her children, in a postpartum leakage of tenderness.

I found this intrusive and condescending. Sure, it’s a weird time, but writing that down is a choice. I have had students for whom I extend care, collegial respect, and sometimes even tenderness; but this is vastly different from the intimacy with which I regard my small children. What is the difference?

Adult students as children is something like the bossman saying “We are all family here” in what is a fundamentally unfair extractive wage labor arrangement (also true for the housewife, minus wages). I am especially salty because there was a recent scandal in the medical academy chatter, when the New England Journal of Medicine interviewed Dr. Lisa Rosenbaum, Harvard Medical School faculty, where she defends her controversial op-ed against resident wellness (which, as far as I can tell, are essentially sick days?!) She likens medical trainees to her children, because “Good parents allow their children to struggle.” Reader, the median age of a medical resident is 28 years old. Besides being patronizing as fuck, what does any of this have to do with workers being entitled to time off for their health?

I came into this culture (what to call it? bourgeois professionalism? passive-aggressive middle management? the darkest side of the PCM?) later in life; it demands one to distort and adapt to a specific flavor of internalized subjugation, in order to maintain a tenuous grip at the feet of the ruling class. I am proposing there is an ominous continuity from the 19th century bourgeois consignment of upper class women to the domestic sphere (a world of ruthless court intrigue, with the high stakes of acquiring and maintaining material wealth, as any Jane Austen fan knows) with contemporary middle management, especially in industries dominated by the “nonprofit” savior ethos, which has long been the domain of colonial wives. This is a high-context coded world, where theatrical sentiment is a tool, and you use what you have. This ethos is unsaid, but reinforced in the universities, medical journals, across the media subsidiaries, to ensure everyone gets in line, if we want a chance at housing and health insurance.

(What will we teach the children?)

Columbia University, where Jamison teaches, is no benign meeting ground (as we have increasingly seen). It is prohibitively unaffordable. The institution lures talented students without wealth via the promise of social mobility and inadequate financial aid, in order to perform diversity. Like many institutions, Columbia’s graduate master’s programs (especially in the arts) are revenue cash cows, hurtling students into steep 6-figure-debt with no plan for future return in precarious industries. Like many universities, it has acted as predatory enterprise following less the ideals of truth, more the logic of infinite growth, exploiting student tuition, federal student loan funding, and nonprofit status to leach land, money, and minds, tangling these massive endowment assets in arms manufacturing. It has retaliated aggressively against workers who even hint at saying Palestine and deployed violent agents of the state to beat its students, at the behest of its ruling class donors.

The Latin translation of “alma mater” is nourishing mother.

Fallacies

Jamison is arguing with great eloquence and skill, that the mother also desires: enjoys sex, craves a cigarette, lusts for success.

No shit?

There is an elaborate taxonomy of rhetorical tricks that derail the truth. Setting up an argument no one actually believes, then battling it with flourish, is called The Strawman.

What does this memoir add to the dazzling rage, filthy eros, and body horror of Ali Wong’s 2016 comedy special Baby Cobra and 2018 follow up Hard Knock Wife? It is not that Jamison’s life experiences are any less precious, vast or complex—but she has the massive capital of our attention, and this is what she wants to say? Seems small.

Sure, it is less small than broader culture, where mothers’ desires are consumerist: house cleaning equipment, a little “something nice for her,” boxes in which to arrange other boxes, or individualist escapism (regional variations in media include wine moms and pinched bourgeois polyamory).

(Look, we all need respite, it’s just, can you tell freedom from an hour of outside time?)

In episode 16, Marge savvily trades Homer’s pants (a coveted vintage treasure), for a paper bag of $2600 cash. She considers the household expenses the money could solve. Then, recalling how disrespectfully her family takes her labor for granted, she defiantly purchases fine jewelry instead. The ring tortures her. She is self-conscious. She hides it. At some point Homer finds it, offended that she had used secret money so selfishly. Then he thinks about all that she does: raise three children, housework, attend to all his crisis, repair the damages he inflicts. He gifts her: her own ring.

This is for over a decade of 70+hour/week of on-call, highly skilled, unrelenting labor. $2600. Are we meant to be moved? Unsettled? The want is so tiny, the portrayal so extravagant.

This is more nefarious than The Strawman—such a portrayal shifts expectations for the rest of us. Sure, some people really experience desire this way, have internalized self-erasure, make art that might contest or embrace it. But on a large platform, it compels the rest of us to ask for less too. Yall are scabs at the femme labor picket line! The source of the misogyny, of the constraining forces, are invisible; what is visible is only the drama of navigating within it—is it criticism, catharsis, or reinforcement? This shit is churned out, year in and year out, in mass storytelling and myth making, mountains and mountains of book-club mandates for self-shrinking.

Why is this all so familiar? I realized: ooooh I’ve been on this shit before. Or at least, quoting other people’s shit about it:

“Namwali Serpell describes the witty, unmitigated, unapologetic desire in Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s W.A.P. ‘The whore—or colloquially, hoe—does want…being not just ready and willing but actively ravenous.’ The transaction is all above board (‘I don't cook, I don't clean. But let me tell you how I got this ring’). Everyone gets paid, everyone has fun. ‘Cardi issues her wants as demands, the directness of which bestows agency to her even when she’s on her knees.’ These Millennial Rappers’ lavish, extravagant gushiness of want is in stark contrast to the narrators of the Millennial Sex Novel. The latter is ambivalent, ‘stuck in a whirlpool of want, circling a vortex of desires. Sexual desire is almost preordained to be ‘problematic’…Ostensibly this kind of female desire is edgy because it embraces shocking, scandalous desires—but they dovetail with the stereotypical desires of powerful, straight men. These erotic trends symptomize and fetishize the millennial’s economic precarity under ‘Daddy.’ Far from BDSM, with its aristocratic origins and contractual/consensual logics, this is a suburban, shame-ridden paradigm, in which the choices are choke me or coddle me, but notably never compensate me.”

Jamison, Emily Gould, and many more, are further iterations of the Millennial Sex Memoir, midlife version. Motherhood’s gendered, material labor only figured tangentially; these texts are first about bourgeois femininity, about squirming under the compulsion to be desired, and never to desire. Perhaps once, in the Protestant hey day, this desire could be subjugated and projected on to God. But now the heroine is resigned to project onto (usually) a human man, who may or may not measure up to the ambition, or appetite of that desire. If you are lucky, Homer Simpson will gift you back your own ring, and you will be grateful.

One of my favorite critics Moira Donegan tweeted:

“The thinking here is that fat women’s bodies evidence appetites fulfilled, and that thin women’s bodies evidence disciplined self-denial, and that heterosexuality will only reward—or perhaps can only accommodate—a femininity that’s essentially masochistic”

“… The sexual allure of the thin woman is not, I think, about the actual aesthetics of her body, so much as the physical evidence of her compliance.”

The sex→food connection of appetite is not tangeential. Jamison herself has written specifically about her eating disorder and women’s pain. Kristen Malone Poli, in her delicious essay “Mythic Appetites: On Meta-Desires, Marriage, and Meals in the Personal Essay”, dissects Splinters among the “divorce canon”, finding Jamison’s “commitment to hunger as a literary aesthetic betrays a connection to the plate, which limits her ability to describe her desires…”

Look I am not here to shame the masochists and ecstatic ascetics—enjoy it, heck yeah! Let Mother tell you what you want. These particular literary versions, though (in contrast to Krause, Ernaux, Wong, and the other Abject Women), are waffling, joyless, and sometimes (Gould’s essay, Molly Roden Winter’s More) ring more as a worrisome cry for help, but ok! The real issue is ubiquity; the chart-topping prevalence doesn’t just shame alternative ways of desire; the way it is packaged over and over, bending the discourse, erases the possibility of other desire. Hegemony is a bitch! Poli:

“Some critics might wonder if these semiotics, which combine the ‘starving artist’ of myth with the self-depriving mother of materiality, contribute to a collective inclination toward disordered eating and thought. After all, if the deep-thinking, MFA-earning, chart-topping literary stars Leslie Jamison and Emily Gould are continually hungry, what does that mean for the rest of us?”

Poli precisely identifies that this kind of book is regressive, in a world in which we are discussing genocide, empire, mutual aid, and family abolition:

“If marriage is used as a metonym for misogyny, and hunger for desire, the actions of individuals who create and reproduce these states are obfuscated entirely. After thousands of words, thousands of dollars, and dozens of hours spent in couples therapy, we are left at the ends of these essays with two women who have committed themselves to doing a little less care work. It is likely that they will feel a little less guilty about doing a little less mothering. Admittedly, in writing these essays, they have taken major steps forward in pursuit of their artistic ambitions, and to no small effect. I have no doubt that Splinters will be a bestseller, and that Gould’s new advice column for The Cut will earn her legions of new fans. That said, the final image of these authors within the context of their essays does not appear to be that of Odysseus, the heroic ‘man of exploits’ they both so revere, but rather of Penelope, granting herself a few extra days of PTO.”

I studied Jamison’s memoir and related for the last 6 weeks because she is “the greatest nonfiction voice of our generation,” an industry gold standard. The literary chatter had been on Jamison, Gould, millenial women’s midlife crisis and similar for months. This is the most depressing topic I have deep dived into in the last 4 years, even though I spent many months deeply immersed in the Sri Lankan Tamil genocide, the horrors of early industrialization, and Andrea Dworkin’s take on sexual violence. In these other horrors, there is always a resistance, a defiance, and a solidarity. But these particular “discourse candy” books have the feeblest sense of that. Maybe it has always been that way. This is more than a matter of taste. I honestly cannot tell if these works are trolling, cynically playing a market, or depressingly earnest. Whatever it is, identifying the hegemony and its boundaries reminds us to look elsewhere.

Mother in the World

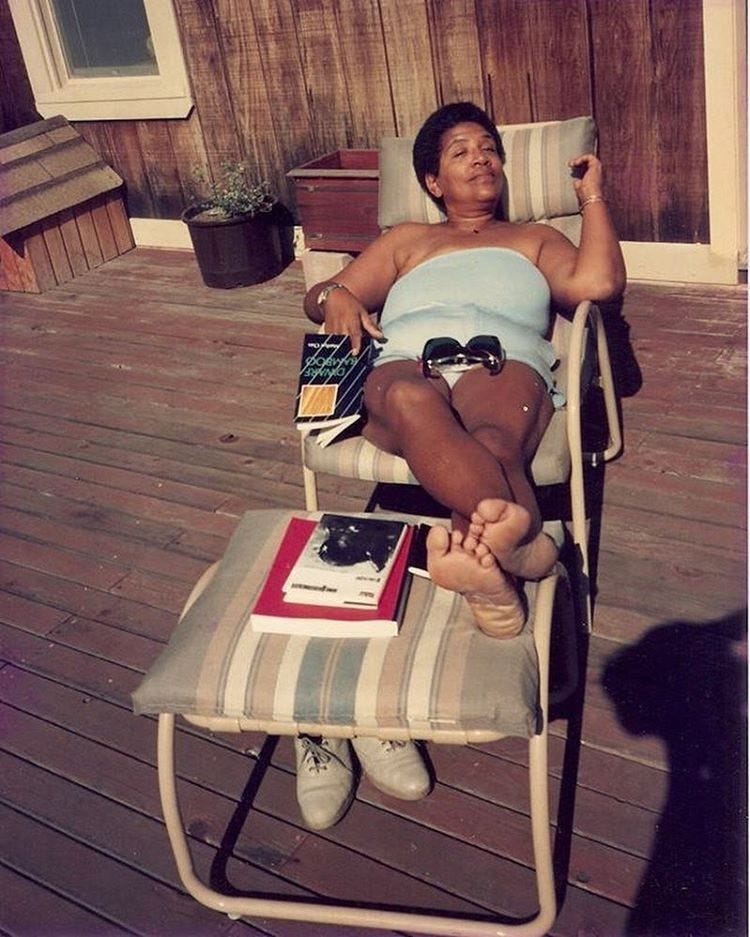

In 2018, when I was drowning in infant and job, Parul Sehgal had already pointed out the homogeneity of the most hyped Mother genre. Angela Garbes (of the excellent Essential Labor) listed many contemporary literary mothering books by women of color, like Camille Dungy. Lists now exist of books that frame motherhood in its political and social context. Fresh editions have hit the press, of a prior generations’ radical feminist literary canon on motherhood, by Adrienne Rich, Alice Walker, Ursula K. Le Guin, Audre Lorde, and Toni Morrison

Everyone is of course, born. Everyone requires care. This is not a niche topic.

Robin Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, wove motherhood with botany, poetry, the land and indigenous history. Kimmerer also wrote about rupture in the lineage: when mothers and grandmothers are displaced from the land, their community, their sense of home is fractured. That absence for me was once a low hum, but became a gaping yowling hole once I had my own children. I was frantic—I cannot carry all of that to them: the language, the stories, the sense of home in your bones when you hear Tamil chit-chat while eating fish curry. Diaspora and exile carries its own neurotic melancholy, but I had strayed further than intended from my immigrant community. Turning to books for comfort and finding primarily isolated bourgeois American motherhood was excruciating. Kimmerer was a respite. She captured pain, but also expansiveness. She teaches Potawatomi to herself, and gardening to her daughters. She grounds motherhood in something much bigger, beyond the small unit of ego and demands-of-child; she grounded it in history, community, a lineage of ancestors, and the very ground itself: Earth, Mommy Ultimate.

Sons and Daughters

Rebecca Walker, daughter of Alice, wrote another side (“With a few small power plays…a mother can devastate a daughter.”). A mother is never telling only her story, Merve Emre says, “Every marriage plot is the child’s bildung.”

“Your child is and is not an extension of yourself. He is both an intimate and a stranger. He imitates you and he rejects you, and it is not always possible to anticipate which gesture is more startling. You can attempt to control what he does, to a point, but you cannot control what the world does to him, or how he responds to it. What we learn from our children is nothing less than our own limitations—our passivity and our susceptibility when faced with what was once a part of us, but is, ultimately, other to us.”

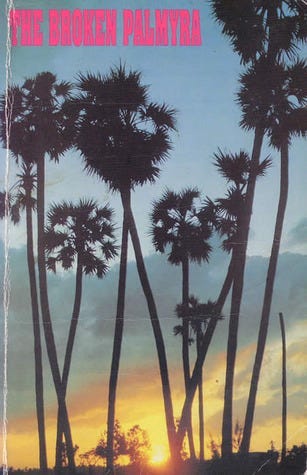

This is true for everything the adult does—you make a decision on behalf of another, decisions with profound consequences. The primary drama of Jamison’s memoir justifies wanting, in decisions that have boring stakes. Dolores Huerta is torn between the children and the the work of the people. Is this Mother vs. “Activist Monster,” when in fact, all the mothers and children’s fates are tied together, in a world that would relish in our destruction? Rajani Thiranagama, a physician and human rights activist, worked tirelessly to document atrocities, co-authoring The Broken Palmyra, one of the definitive accounts of the early Sri Lankan civil war. Atrocities committed by both the government and LTTE forces, were meticulously gathered and fact checked, from the people who experienced it. Within weeks of its publication, she was assassinated, leaving behind two daughters, age 9 and 11. Was that the right thing to do?

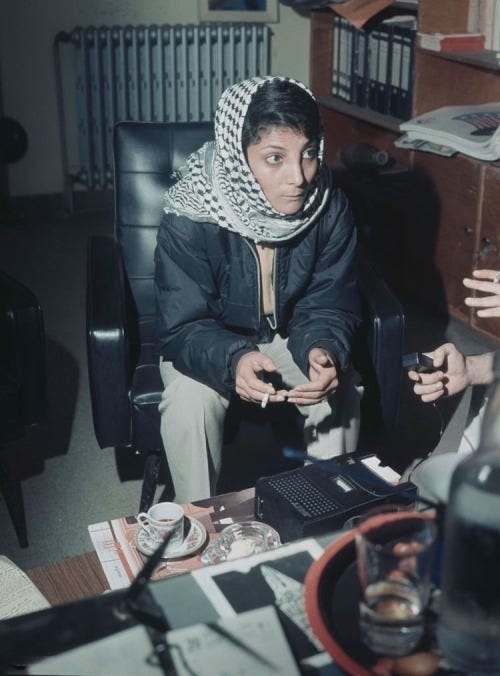

Leila Khaled, Palestinian socialist and teacher, was exiled to Lebanon at age 4 during the Nakba. She would grow up to join the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (for which she was imprisoned), then the General Union of Palestinian Women, and cared for those injured in Palestinian refugee camps, by Israeli attacks. She said about women’s work in building a future of sharing land in harmony:

“Women give life. So they feel the danger even more than men. When they are involved, they are more faithful to the revolution because they defend the lives of their children too. When I gave birth to two children, I became more and more convinced that I had to do my best to defend them and build a better future for them. I felt for women who had lost their children.”

If all the world’s mothers had boring stakes instead of mortal risk, that would be a better world. It’s not that only frontline revolutionaries can tell good stories. Nor that only WOC should be burdened to speak of strife. Only that making sense of the world and home, child and parent, other children and parents, is part of motherhood too.

Hero Artist

The Art Monster is the flipside of the Hero Artist – an individual, a Great Man, the genius who must forge the path to illumination, alone. The work is most important. Someone else must wash the dishes, feed the children, edit The Great Work. This is the contemporary imperial sense of self. Of course the artist mother becomes a twisted knot if framed as artist mother, Mother Hero, Mother Monster.

Choice, or “I would prefer not to”

A couple years ago, a little after the delta variant, after my hospital had run out of ventilators, when the region played hot potato with gasping bodies as ambulances drove circles in desperate search for a bed, when the daycare had opened again for “essential workers,” but cut hours and sent children home on 10-day quarantines, when my toddler howled and the baby nursed all night after 16-hour workdays, while my partner burned out amid missed work and piling domestic tasks, when we ate spaghetti with bottled sauce every night, when i felt moment-to-moment as if being boiled alive, I complained frequently into the void of my private Instagram stories. Admittedly it was less complaint, and more (increasingly unhinged) howls. At one point a college friend texted “but you chose this.”

It effectively arrested my rage—I stared at the screen, baffled, laughed, finally texting back: “Go fuck yourself.”

I chose a fight and it felt good. It felt better than the bewildering diffuse miasma of “the system.” This too, is too small.

Bodies Bodies Bodies

Which brings me to SotA, a week-long art residency in Black Mountain, North Carolina, from where I recently returned. Embodiment is a thing I had heard about, but vaguely. I hadn’t really thought about it, but there, I had been invited to. So I said yeah, sounds right, sounds fun. I felt emboldened to experiment, by the vitality, the brilliance, the care, the play that I encountered. I would go on a walk in the woods and feel my body!

Things went awry.

Initially, it was great. The mist speckled my face, I heard the erratic chorus of insects, frogs, running water, and my nostrils tingled with multiple flavors of petrichor. Fantastic! Very Good! So Nice! But over the following day, I felt unwell, shaky, tired. Well, I probably was tired! Maybe i was just feeling how tired I have been all along. Then shit got very shaky. And weepy. Very very weepy. Convulsive sadness and grief, of horror, of isolation, of mortality, about the ruthless evil of empire and the mundane tragedy of feeling misunderstood.

This went ON. Between classes, kitchen duty, & beautiful convos, I walked miles in fugue, sometimes in the woods, sometimes aggressively pacing the cinder-block dormitory halls. At dawn, I stormed up and down the campus hills, the birds in perfect cacaphony, so loud, so bold, so steady in their collective. I tried to journal, I tried to talk—what is this about? I had ideas. I stared at the grief altar, pulled the tarot, gave in to music’s rapture, slept a little. I missed my children desperately; I relished my freedom from them, also desperately.

Dramatic, I know! What can I say? Throughout, I also felt so clearly the other side: voracious desire, hunger. I encountered beauty anew. I devoured full plates of food, in awe, that someone had made it, someone grew it. Look, I have been hungry and satiated before. I’m just saying: numbing pain also means numbing everything. There’s always leaking and overflow, but unclogging all the ducts is a whole other setting. I am not even sure it is sustainable. It was like a cheesy college drug trip, but like 5 days long, and brutally raw with the grief accumulated over decade(s). Though there was not mere catharsis, but also connection.

Uses of the Erotic

Audre Lorde’s On the Uses of the Erotic: desire is a profound power. By heeding it, you trust the body, as a finely-tuned and wise perceiver. If you do not know what good feels like, what are you working towards? How will you even know if you get there?

Someone led by internal desire is legible. You sense and react to them—your bodies read each other. But someone with disciplined, numbed, and unsaid loyalties is evasive by design—to whom do they submit, why, how far? If they are not attuned to their own desire, how could they respect ours? How do they calculate what is worth proximity to power? The imprisoned one expects others to also be imprisoned, because they cannot imagine otherwise, or they cannot imagine anyone deserving otherwise, or they cannot imagine that if they, with all their rank, don’t deserve it, how could you possibly deserve it. They sell our own subjugation to an impoverished imagination. Do not consent.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: “The great tragedy of humanity wasn’t that we die or suffer or make each other suffer. It was that we forgot. And because we are so prone to forgetting–because it is so easy to make us forget–we accept the conditions of our suffering as inevitable and cannot fathom alternative.”

Weeping amid comfort and safety in an art residency is dramatic. But today, I felt the paroxysms of horror work its way through the social fabric, as we collectively metabolize the atrocities, for which words fail, yet again (again, again, again) in Rafah. The unimaginable numbers of displaced people amid genocide in Congo. The displaced and besieged people in Sudan. Literal millions. We feel them, we feel how we are implicated, we know (this is also what they did to our grandmothers); we feel fury, we feel desperate, we tear at ourselves in frantic prayers. I feel it while I make dumb power points for work, load the laundry, bloggity blogs, sort mail, pretending not to feel it. This seems much more dramatic, much more grotesque.

Violence is also a type of desire, touch, a sensuous reaching towards, a yearning, a possession, blood lust; even as it severs, subjugates, destroys. It forces us to react on its own terms: fight, freeze, flee…or submit and propagate, hoping that it will keep you safe—even as the jeering soldiers committing heinous acts make clear: “We will kill you without restraint and no one will stop us. One day you will all be Palestinians.”

So then?

It is easier with each other—a revelation that is neither deep nor pretty, I know. Shit is so volatile and outrageous, the distractions so cretinous, we have to go back to the drawing board over and over and remember what is true, remind each other what is true. Here you are, this beast that fears and wants and loves. Here we are. This is what we want.

Keep going. We must imagine Marge Simpson happy. Who could not imagine the happiness of a cycle? Kiss the children, dress the wounds, adore the lover, plant the garden, bless the dead. Again and again and again, each season, each moon, like the sea. Leave the boulder, find the choke points, read the books, befriend the ones (who mind the levers). Lock eyes, bring the coffee, play some games, block the commerce, wash the cups, withhold the labor, pull the threads. It’s all been done before.

*

Thank you SotA people, with whom I communed, for the astonishing invitation, to perceive and be perceived <3 Thanks to my man, who feeds me, whose love and care and adventure expands the world <3 Thank you to my children, who have not yet forgotten how to be, for all children, who deserve peace, joy, and the swift, definitive end to empire.

I'm so glad you included Leila Khaled's story. There are so many Middle Eastern women who have been either forgotten or erased, yet their contributions have been immense. Take Jamila Buharid, another resistance fighter from Algeria (whom I wrote about), who shares the same reasons for her battle as Leila Khaled. Motherhood always has a negative societal view regarding a mother's involvement in political issues, yet history shows the contrary. A mother will fight twice as hard for her country as her fellow countrymen for the sake of her children. Thank you for sharing this informative piece.