Part II: the Psychological, the Sociological, and the Nonfiction "I"

Did you know sometimes moms like to have fun? Myriam Gurba, Immigrant Parents, Guernica, and other revelations

Solidarity with the community, students, staff and faculty protestors. Please consider supporting:

Open letter for Wash U

https://atlsolidarity.org/

https://secure.actblue.com/donate/bailfunds

This is Part II of an extended review of Leslie Jamison’s recent memoir Splinters

Part I: Envy and money.

Part II: the Psychological vs the Sociological -> you are herePart III: Aesthetics vs Ethics

Part IV: Paranoid Reading

Part V: Mother

(The outline will continue to evolve, depending on stamina)

I buried the lede but, I didn’t like this book. It was well-written and boring.

I can only consume a finite number of cultural objects with this one wild and precious life, and this took some of it. Instead of moving on, I have spent additional life creating this long response to understand why. A response that invites questions like: what’s the money math that facilitates rambly blogs? (day job, low cost of living, an anxiety disorder soothed by compulsive writing)

To Jamison’s credit, she crafts recursive inward spirals with clarity, and I…cannot. So this is an outward spiral: an argument from taste to political—a treacherous path.

Every once in a while, despite my studiousness, I have this revelation that books, book chatter, this writing world, the academy, its cheese platters, twitter beefs, oblivion to student loans...is not for me. It is provincial, but because its population holds the means of cultural production, all of us are disproportionately subjected to its insular tastes. Jamison’s book, which I had only wanted as entertainment to endure isolated domestic labor, reminds me of this.

The relentlessly autobiographical

Jamison is aware of the structural issues at play. In multiple interviews, she describes research she has done, e.g. history of divorce. This “different kind of love story,” shows her shift the emphasis from seeking the approval of men (her father, ex-husband, boyfriends) to her daughter and the mutual care of women in her life (mother, friends, mentors; the nanny and divorce lawyer too, for fees). But Jamison has said in interviews, that this “text felt allergic to these inquiries;” she instead followed the “heat” of the autobiographical.

What shaped that heat? What is hotter than the pressing political and social crisis of our time? About women’s experience post-Dobbs v. Jackson? Whatever it is, the result is a claustrophobic work.

Perhaps this is intentional, to convey the claustrophobia Jamison herself experiences in romance and parenting. Misogyny and the privatization of the domestic realm are key pillars of the current regime, and these are enforced interpersonally, as well as systemically. Contemporary parenting is exhausting, in its demand for both moneyed and uncompensated care labor; the vigilance required to navigate spaces that prioritize cars and commerce over children and families; the difficulty in maintaining supportive networks of friends and family across space, time, and demands.

This shrinks one’s world and cleaves one from civic engagement. Confronting a militarized police force is a more difficult calculation when, in the nuclear family, there are, at most, 2 of us immediately accountable to the care of our small children.

(It is also in caring about small children, that renders mobilizing against violence towards them and those who love them, more urgent—as it should. That isolated care labor impedes connection and organizing, makes the nuclear family and Dobbs v. Jackson that much more ominous)

Marriage too, has long been structurally weaponized to deploy law and culture to confine women (of a certain kind) into a constricted domestic sphere, where one woman is expected to do the work of 20 (or oversee the work of 20 underpaid other women). Besides the material toll of this labor, the primacy of marriage places a heavy interpersonal burden on romantic relationships, which must do the work of 20 other kinds of relationships—co-parent, lover, roommate, artistic collaborator, friendship, co-executives of the household firm. These are the unearthed expectations of American heterosexual bourgeois womanhood with which Jamison repeatedly collides.

Jamison of course, doesn’t talk about any of that. The pain of these collisions, though, is beautifully observed: “Trusting the stories I told myself about romance made me feel like a moth stubbornly ramming itself against a flickering bulb. The bulb would never be the moon. The marriage plot would never be the moon. Eventually, the moth would sizzle its wings against the bright glass, or else die of exhaustion.”

But Professor: why did you believe that, who set up the bulb, who obscured the moon? Why do we care? Jamison is exemplar in capturing embodiment and emotion in pretty words, but the explanatory grounding is elusive. It isn’t that I need Jamison to cite Marx and Federici in her love story (though I would enjoy that) or a detailed Austean expose on her elite literary social circle (a delicious spectacle, but probably unimpactful) or piously recite a litany of inclusivity clauses, as tedious inoculation against criticism (Me! but also, consider the WOC, the poors, the disabled, the queers…). This unabashed tight focus on the individual and her small social sphere is unmoored. Adding cliche homage to NYC only emphasizes what’s missing (drawing more focus to how that NYC rent gets paid, and absence of the service labor that holds it all up).

Becca Rothfeld’s review of Splinters does not criticize Jamison’s money vagueness, but vagueness in general. Like Kanakia, Arn, Taylor, Rothfeld is also dissatisfied with the low stakes. Rather than class sensibility or inadequate world building, Rothfeld attributes this to solipsism (“gruelingly and uninterruptedly autobiographical”) and homogenous styling (“everything is invested with the same drenching importance”). She roots these sins in therapy-speak.

Psychologizing

I see what Rothfeld means. Jamison’s conclusions are...unsurprising truisms: wanting help, pleasing Dad, feeling pressured to be married (by whom? for what?), exaltation in work (“writing was my great love”). She loves her mom and daughter. She feels empty: “the only thing I ever wrote about: the great emptiness inside, the space I’d tried to fill with booze and sex and love and recovery and now, perhaps, with motherhood.” Does she think this emptiness unique? Consider:

“The possessing class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-alienation. But the former class feels at home in this self-alienation, it finds confirmation of itself and recognises in alienation its own power; it has in it a semblance of human existence, while the class of the proletariat feels annihilated in its self-alienation; it sees therein its own powerlessness and the reality of an inhuman existence.”- that guy, Karl Marx

That emptiness powered a lot of book sales. “Much of the sentimental lexicon in Splinters,” writes Rothfeld, “appears to be culled from therapy, and indeed, Jamison reproduces snatches of conversations she had with both her therapist and her erstwhile couples therapist on more than a few occasions.” Who can judge any of us when we grasp for help to navigate our mundane miseries? But why are we, the audience, enduring Jamison’s mundanity? We have plenty enough of our own.

The failure is not inadequate “pedestrian language” of therapy-speak; this can’t be rectified with better psychological language. The problem is centering the individual psyche at all.

Borrowing from Taylor (adamantly not-a-marxist), storytelling only makes sense when we stop omitting the material world, peopled by others, organized by society. But Jamison is trapped in a literary tradition of individual psychology, a tradition she exemplifies.

Revisiting “The Empathy Exams,” this is already glaring. In that essay, Jamison accepts as starting point, the medical psychological framework, itself a feeble, bastardized descendant of Freud. When she expands a Standardized Patient’s back story, she refracts even intimate relationships back to the self. She sees empathy as excavating the psychological causality shaping the self.

“Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see: an old woman’s gonorrhea is connected to her guilt is connected to her marriage is connected to her children is connected to the days when she was a child. All this is connected to her domestically stifled mother, in turn, and to her parents’ unbroken marriage; maybe everything traces its roots to her very first period, how it shamed and thrilled her.

“Empathy means realizing no trauma has discrete edges. Trauma bleeds. Out of wounds and across boundaries. Sadness becomes a seizure. Empathy demands another kind of porousness in response.”

Despite Freud, this is a very deterministic, mechanical account. In any case the medical student is not there to excavate a patient’s personhood; she is tasked with diagnosing and treating the gonorrhea, then moving it along to the next 20 patients.

Empathy is a kind of care, but is neither necessary nor sufficient. When Jamison herself is in pain, she initially desires someone to excavate this pain and mirror it back. “I needed people—Dave, a doctor, anyone—to deliver my feelings back to me in a form that was legible. Which is a superlative kind of empathy to seek, or to supply: an empathy that rearticulates more clearly what it’s shown.” Dave the boyfriend is a steady bodily presence at the bedside, the doctor is there to complete a procedure. The kind of person who makes feelings legible and delivers it back to you, might be a generous friend, but usually it is a therapist.

Jamison eventually concedes that she doesn’t need a doctor to mirror her feelings; instead, she appreciates Dr. G’s co-regulation, as the tiktok pop-psych descendants might say—his calm assurance, rather than mirroring her distress. She acknowledges there are other kinds of interpersonal care. In Splinters, 10 years later, Jamison talks about love for the other (daughter, mother, community), but the form still refracts all this back to her own interior. Which is, by most social conventions of storytelling, a weird thing for a person to do!

An Aside

I don’t know where this fits, but can we talk about the cardiologist in “The Empathy Exams”? There are 3 doctors, less people, more stand-ins for ideas (a technique repeated in Splinters, but with boyfriends). The cardiologist is a curt older woman who represents the scripted empathy that Jamison criticizes. Jamison called the cardiologist, to notify her of the abortion scheduled before the ablation. The cardiologist paused, and said the equivalent, of “ok?” Jamison felt dumb and started crying on the phone. Which you know—is there anyone who a cardiologist hasn’t made cry? One or another cardiologist has sent me sobbing in the stairwell at least biannually during training.

What’s funnier is that the cardiologist returns to Jamison weeks later, when the latter is laid out for her cardiac procedure, anesthesia kicking in, to stiffly apologize for making her cry, because Jamison’s mom called and confronted her about it. This, for me, was a striking detail. I get that healthcare is a nightmare dystopia, that family can be the last line of advocacy for vulnerable patients…but I can’t imagine calling my child’s doctor and complaining that they were…impatient? Especially if that child is an adult?! Jamison does not forgive the doctor: “I wanted to tell her I didn’t accept her apology. I wanted to tell her she didn’t have the right to apologize—not here, not while I was lying naked under a paper gown, not when I was about to get cut open again. I wanted to deny her the right to feel better because she’d said she was sorry.” I think the cardiologist knew exactly what she was doing.

An Aside to the Aside

Who am I to question expressions of maternal love? Maybe those of us with traumatized immigrant parents should probably learn from Leslie Jamison’s mom and break the cycle. Ruth Madievsky has an excellent portrayal of the baseline in I AM YOUR IMMIGRANT PARENT AND YOU WILL ACCEPT MY BYZANTINE DISPLAYS OF LOVE

“I see you’re having an excavating heart-to-heart with your American friend about her childhood trauma. Here’s a plate of cut apples. Make sure to eat the skin; that’s where all the vitamins are. Stop crying, Shannon—your tears are washing the vitamins off.”

Counterexample

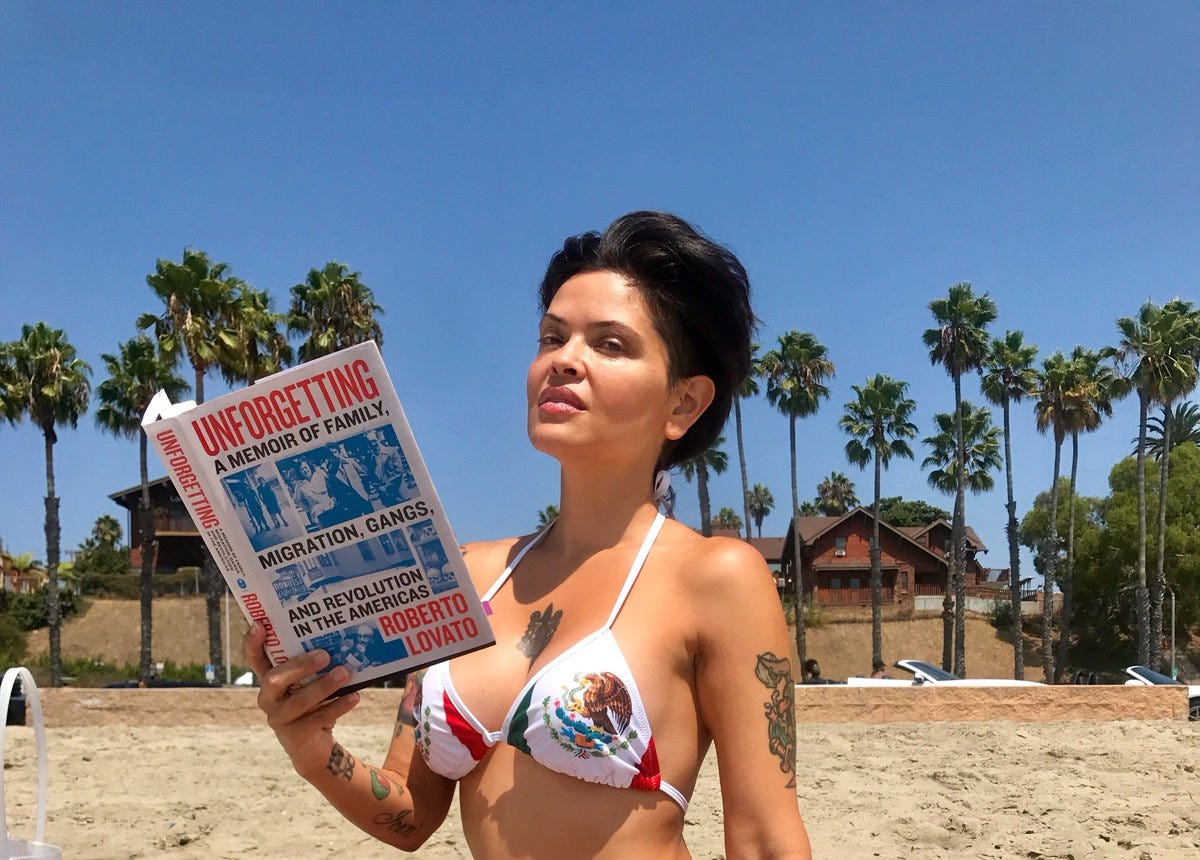

Contrast this memoir with Myriam Gurba’s essay collection, Creep. Like Jamison, Gurba is a lauded Californian, a woman, witty, a middle-class writer and educator, raised in a family of writers and educators. Gurba, like Jamison in previous works, weaves memoir with larger excursions: family lore, histories of Mexico and California, true crime, court cases, literary criticism. She uses these to build an intricate argument, both logical and emotional, about the ways misogyny is violently nurtured and enforced. Gurba is nuanced; she considers violence against women while holding the humanity of men, shifting emphasis from the interpersonal towards systems of law and culture. There is no facile psychologizing. She does all this without moral muddiness: there is no apologia for those who harm others, including herself. She holds both understanding and a clear position. You may disagree with the position, but you know what it is, which allows for explicit argument.

And possibly a fist fight. Perhaps revealing the law school ambitions of her youth, Gurba’s charismatic authorial voice has a jovial combativeness. Her voice sounds like it will stand with you on the picket line or back you in a street fight. Maybe this is not craft, but from the IRL stories of Gurba legally confronting a violent ex and school leadership to defend her students. Jamison’s authorial voice conveys gawking at pain, nodding sympathetically, then going back to the hotel room to probe its impact on her; which is literally what she has described doing IRL. Make of that what you will.

Gurba’s essays are also richly peopled. Jamison’s people—the ex-husband, mother, ex-boyfriends, friends—are often nameless ciphers. No matter the feats of precise observation, conveying that the author has Considered Their Side of Things—the others are primarily stand-ins for ideas, relevant only to the narrator’s evolution.

Gurba renders vivid 19th century politicians, serial killers, a swaggering misogynistic grandfather, a grandmother’s thwarted ambition, an ex-girlfiend’s whole rural Midwestern family, the smartass teens that linger in her classroom. Even the coastal fog evokes sentience. She creates scenes and conjures conversations. On William Burroughs shooting his wife:

“When William noticed a small blue hole in Joan’s head, he screamed, ‘No!’ He jumped into her lap and chanted, ‘Joan! Joan! Joan!’ Maybe he wanted to be consoled by her. The living expect a lot from dead women.”

Despite her delightful criticism of Didion, Gurba’s writing belies a similar exhilarating vibe, of the smart mean girl, one who is perceptive about the cruelty of the world, and can coldly hold its gaze.

Gurba’s essays deploy storytelling, persuasion, jokes. She acknowledges her beauty and education, with the sharp intuition of a standup comic, forged by hostile rooms—grant what people see and what they presume, so that they can move past it to hear what you have to say. With Gurba, you sense she has brined deeply in the interrogation, generously sharing its richest fruits (pickles?), with the mastery of an experienced teacher. She entertains, illuminates, charms, and discomfits the reader. She invites and addresses you.

The “I”

Culture critic/English professor Merve Emre, in “The Illusion of the First Person,” grounds the evergreen cycles of “the-essay-is-naval-gazing” and its passionate rebuttals, into a multi-century conversation. She argues the contemporary essay has diverged from its history primarily in the way it has carved out the “I” from the “We.” Emre pins the divergence on Charles Lamb’s 1823 Essays of Elia. Various scholars describe this collection as “quintessence of the spirit of bourgeois intimacy” and capturing “a single subject whose identity is defined by the uncontested readability of his proper name.”

This was after all, very shortly after the French Revolution, when the Bourgeoisie (the craftsman, artisans, merchants) dispensed with the feudal and royal classes, who had been for centuries, overcharging on rent and taxes. Flush with the wealth of global trade (i.e. violent acquisition of goods, land, forced labor via colonialism), this group valued personal liberty (the “I”) and efficiency (e.g. the guillotine), procuring rights for themselves, and at least on paper, for the lower classes too: liberté, égalité, fraternité. Then it was the industrial revolution, and we know how that went.

(We actually don’t, thanks to a century+ of American propaganda, but tl;dr - the haute bourgeoisie have established itself as our new feudal lords, with the petite bourgeoisie (or professional managerial class, if you will) as its attendants).

Virigina Woolf was an early hater of the modern essay (“The Decay of Essay-Writing,” 1905), blaming mass education and media for crowding the public with too many “I’s”. Emre described her “boredom of having to attend to ‘a very large number’ of people, all of whom demand public recognition through the projection of a private interiority.” Dang, Woolf, you would hate to see how that went.

Emre continues: “the personal essay…is the genre whose formal conventions—the ‘capital I’ of ‘I think’ or ‘I feel’—not only draw the individual into public view, but also insist upon the primacy of the individual,” when it is actually the social that is precedes the individual. Woolf deplored the “amiable garrulity of the tea-table” (like Arn’s disdain for the tipsy bourgeois dinner table), with its self-obsession of “individual likes and dislikes.”

(Who does get to have public recognition, Virginia? Emre doesn’t address this elitism here, though she might in her book).

Taken together, personal essays do not cohere, which is also what Rothfeld criticizes about Splinters. Emre summarizes, “They [personal essays] cannot be imagined as a mass, a totality, cannot be integrated and set to any collective social or political purpose.” For Woolf (and Emre), the modern essay is too interior. Emre argues that the answer is for the essay to engage explicitly with the tension between the individual and the collective. Emre:

“the essay had to maintain the contradictions between individual desires and social demands, between personal being and impersonal experience, to grant the form its unique ability to capture the texture of life—not a particular life, but the impersonal activity of living.”

I am not fully convinced that the “we” is as useless as the “I” in essay writing; perhaps this becomes a different form—the manifesto?

Accounting for the personal essay boom of the 20th and 21st century is not that complicated, Emre states: it sells. The 2010s online essay boom, primarily constituted by young women disclosing the personal as spectacle, in exchange for small purchase in a precarious industry, was maybe the last written version. This has been transmuted to the breathless disclosure and bald commerce of the influencer (Terry Nguyen’s has a recent summary, though the classic is Jia Tolentino’s).

Even more interesting is Emre’s argument about the impact of the American college application essay, with its explicitly antisemitic origins in the 1920s. The application essay was introduced to counter the increase in admissions of Jewish students after test scores were introduced. The essay and extracurricular list would proffer a “character statement,” a mechanism by which to exclude these students (a familiar reactionary corrective, against even the most minute consequences of meritocratic posturing). Given its purpose, the admissions essay drew on traditions of Catholic testimony and “the moral culture of the Protestant bourgeoisie, what Max Weber described as its use of education to cultivate a rational, self-assertive personality.”

The curdling of one’s soul required to package and pitch the self in admissions essays is that first gateway to social advancement (or maintenance): the elite university. It repeats for graduate and professional school, residencies, fellowships, grants, job cover letters, artist statements, the self as brand. Emre:

“Beyond its discriminatory function, the personal essay sought to identify the students whom the university could transform into the political and economic leaders of the future. Learning how to ‘game the system’ was only a sign of the system’s success at shaping applicants’ behavior.”

Although admissions committees are less explicit about it, the admission essay remains a mechanism by which to perpetuate an exclusive ruling class. That this debate has been grotesquely deployed upside down to condemn DEI with snarling, uncloaked racism, deserves its own essay.

In this type of Christian testimony, Emre describes that “Applicants are encouraged to draw a moral out of a personal anecdote, often about struggle, and enriched by some element of their reading or studies: ‘failure,’ an expert on the admissions essay tells us, ‘is essayistic gold.’”

This is the exact structure that explains the familiar vibe of Splinters, dramatizing the failed marriage plot and its various anodyne confessions (chlamydia, cigarettes; did you guys know moms like to have fun sometimes?). Emre continues, “Far from signaling weakness, the proud narration of failure speaks of character in precisely the terms set by the educated bourgeoisie of the early twentieth century: character as the capacity to maintain one’s self-comportment in a moment of distress, to tell a tale of hardship lit by the glow of self-knowledge.” Splinters’ narrator stakes out violation of mores, self-flagellates, then settles on some bland truism; exactly this kind of “masochistic public exposure and redemption.”

The flipside of posturing struggle and redemption is the suffocating “trauma-porn” demanded of applicants from marginalized communities, who are pressured into performing for gatekeepers. This becomes a spectacle of othered tragedy for bourgeois consumption. It is a weepy vampirism of the projected ennobled suffering of others, something Jamison herself cannily described in her earlier work. The only good thing about this miserable shit, is that it has also created a rich genre of skewering it. Myriam Gurba’s own masterful shred of American Dirt, Radha Blank’s film 40 year old Version, the film American Erasure, based on novelist Percival Everett’s Erasure, Elaine Castillo’s fiery essay collection How to Read, Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, almost anything by Yasmine Nair, but especially her essay “The Perils of Trauma Feminism.”

Public Health

This last essay really set me on a course, because it reviewed Rafia Zakaria’s book about her experience as a Pakistani human rights lawyer in the global NGO complex, dominated by the wealthy women of neo-imperial countries.

A key moment I was knocked off course in Splinters, despite its gripping first chapter, was when Jamison describes that both her parents are global public health researchers. It is funny that Jamison’s book is so claustrophobically interior when raised by public health professionals; public health is almost entirely context and collective (though that too has been dismantled in the last 15 years of behavioral economics).

My whole career—forged in the Obama era of narrative medicine, public health research, infectious disease, global health, American NGOs, empathy—was illuminated by Nair’s description of Zakaria’s disclosures. Nair gave me a language for the performance of it. It helped me make better sense of my early graduate public health work, examining the economics of the global healthcare work force: how WTO-imposed austerity decimated countries’ healthcare systems, then Western NGOs swooped in, to charitably “save” these countries, while poaching underemployed, overworked healthcare workers (trained on the poorer' country’s dime), and locally implementing whatever shady agenda was dictated by donors. The saviorist narrative lacked the money math.

The whole pattern is not so different from the Catholic and Protestant churches of the 19th century, right down to the weepy rich colonialist wives, worrying about the orphans, while their husbands staffed the bureaucracies, militaries, and state-backed corporations (the Dutch East India Company to Dole Fruit) that pillaged and murdered on unimaginable scales. The primacy of sentiment obscured the crimes.

And then there was Guernica, with its own weepy colonialist do-gooder lady, who wrote so prettily about interiority and feelings, while willfully omitting systemic violence. Patterns. Whatever that essay’s failure as art, I withdrew my piece in solidarity with the editors, whose usual editorial procedure was bypassed when the piece was published by fiat via the EIC (the free speechers who fussed about it have been incredibly quiet, while the actual State is cracking skulls to suppress peaceful protest).

Jamison speaks of her parents “do-gooding” with unabashed admiration, even the father who talks at her about economics, oblivious while she struggled with his toddler granddaughter. I know these people. Not specifically, but this type of people, I have worked with them. I have avoided Leslie Jamison’s Wikipedia page until this very paragraph. But when I finally look, it maps out an extended family of elite scholars (including psychologists), mostly incubated through Harvard and similar. The LA she grew up in? Pacific Palisades. This by itself is not enough to lose trust in the work; even a cloistered elite can make good art. But Jamison’s uncritical appraisal of her parents work in the world, her omission of this very specific background while discussing her family, renders me suspicious of what is either: Jamison’s lack of insight on how the world works, or her capacity to honestly portray it. As a professor in one of the countries’ leading schools, she will perpetuate this.

If nothing else, her omission of “world building” explains the blandness of her memoir. In contrast to Gurba’s extremely specific setting of Santa Maria, California, and positionality of identity and family history, Jamisons presumes a universal voice from her own specific history. This doesn’t work because her position is not universal, but actually insular.

What Is criticism for?

I have tried to make sense of this memoir on its own terms, as story telling and personal nonfiction voice, something beyond personal taste. But it’s hard not to make sense of the book without sociological context. In a future installment I’ll dive (probably) into the quagmire of the Aesthetics vs Ethics debate (pray for me). Anyway. Splinters. I am asking too much of this book in the face of atrocity and social volatility. What can this book (or its critique) do, amid the laundry grind and genuine fear of which direction post-empire goes? Not much, but there’s something here, something that made me angry that it even exists.

The consequence of splitting the public and domestic domains (and confining women to the latter) is a significant mechanism of enforcing gendered power—a woman is cut off from we, leaving only “I.” There is more to say about “I” and personal testimony, especially its potency in aggregate (#Metoo) in sexual assault and abortion rights.

It is also impossible to ignore the racial dynamics, that for at least a decade or two, the first person essay had been dominated by white, upper class women like Jamison. Soraya Roberts in 2020 characterized these: “Their essays centered on subjects like gross-out body breakdowns, convoluted sexual relationships, and the peccadilloes of urban life. Tolentino argued that in the wake of the recent election, this sort of personal was no longer political enough to survive. And the argument wasn’t wrong, it was just looking the wrong way.”

Soraya points out the long history Black and radical feminist writers deploying the personal essay as political, and contemporary blockbusters like Roxane Gay. “The Personal Essay isn’t dead, it’s just no longer white.”

I will return to this. Representation is rarely enough; Gay’s early essays were not political. Unlike Jamison, those essays acknowledged the political, but only to reject it.

Despite Tolentino’s prophecies, Jamison continues to churn out this dated boring shit, like the last 8 years never happened, like a literary Taylor Swift. Anne Helen Peterson has astutely described about Swift, that the “prominence of her image [is used] to talk about discourses of girlhood in general.” A successful and ubiquitous artist becomes a canvas on which to project our own narratives and debates. Peterson compassionately diagnoses how Swift (onto which i project Jamison’s Splinters) fits into a larger conversation:

“As a privileged white woman with progressive politics, I understand the frustration: we are generally good at seeing injustice, and we are generally bad at giving up our own sliver of societal power in order to rectify that injustice. What most reliably moves us to act is personal stakes, and the absence of them makes it easy for us to ‘move on’ from causes [Jamison following “heat”] that other people have no choice but to engage every day of their lives. It can feel like white women are only in the fight when the fight is popular, easy, and without significant social or financial risk — and when they do join the fight, they want to be celebrated for it.”

“And whew is that rough to hear! If you identify with Swift — particularly with the Eldest-Daughter, Type-A, highly regimented, no-choice-but-to-be-a-good-girl part of her — maybe it’s even harder. Because it’s about her, but it might also be about you, and it’s also not really about her or you, it’s about a whole group of people grouped with you simply because of their identity, and if that feels unfair, I would suggest sitting with that for a moment. But it also feels unfair because you can try and do everything you were told to do, work so hard to please so many different demands from so many different people, and still not get it right.”

I end with a much stronger claim: If the Jamisons of the world have nothing to contribute to the pressing issues of our time, they should at minimum, stop taking up so much space (for 6-8 weeks, her interviews and excerpts were in every major and minor magazine). Optimally they will lift other, more relevant writers, loudly.

It is too bad discourse (and its associated valuable asset, attention) is often dominated by literary Swifts—people who might be technically good at what they do, but little to add other than book-length equivalent college admission essays, but still take up a lot of space.

The world is full of rich, insightful writing like Gurba’s, Vanessa Angelic Villarreal’s better divorce essay, motherhood writing by Angela Garbes, Camille Dungy, Vanessa Hua, the bourgeois but ruthlessly perceptive Christina Sharpe. These writers are plenty decorated with awards, esteem, and television appearances (though probably still not enough), but command less of the discourse cycle. I myself do not write enough about these books that I like more, because I am not as agitated by them; not because they are perfect, but because I am absorbed into them. This should probably change.

But this is all beyond consumer choices (what is directing one’s attention now but a consumer choice?). I initially titled this section “Psychology vs Ideology” to articulate a debate between the Marxist/sociologist cultural criticism and the “aesthetic turn”/New Criticism insistence that art be considered in isolation. But the bourgeois psychologizing of art is also ideology, not easily rectified by representation from the margins. Once you see it you can’t unsee it (see: Part IV: Paranoid reading) or its political implications.

Next time, Part III: On Aesthetic Fundamentalism (probably) Mother